On November 6, Louisiana voters will have the opportunity to eradicate a troubling vestige of the Jim Crow era: the non-unanimous felony verdict. Even though the drafters of the law allowing non-unanimous felony verdicts acted with admittedly discriminatory intent, the rule still stands to this day. “Mostly guilty” is simply not enough to convict a person for a crime, as recognized by 48 other states. We respectfully urge voters to make Louisiana the 49th by voting “yes” to Amendment 2.

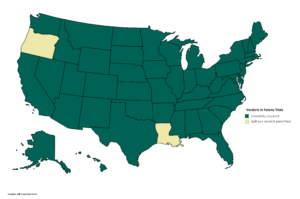

48 states require unanimous jury verdicts to convict a defendant for any felony.

Amendment 2 proposes to require unanimous jury verdicts for any felony offense committed on or after January 1, 2019. 1 Currently, criminal cases tried in Louisiana’s state courts only require a unanimous verdict when the defendant is facing the death penalty.2 All other felony defendants may be convicted by a non-unanimous jury, as long as at least 10 of 12 jurors concur in the verdict.3 Louisiana’s split-jury rule is an anomaly in the United States criminal justice system, where unanimous verdicts are the norm. In federal court, unanimous verdicts are mandatory and non-waivable in any criminal case tried by a jury.4 Forty-eight states require unanimous jury verdicts for any felony conviction. Even Oregon – the only other state that permits non-unanimous felony verdicts – requires unanimity to convict a defendant for murder.5 As such, Louisiana is the only state that will allow a non-unanimous jury to convict a defendant for any noncapital felony offense, including those punishable by a mandatory term of life in prison.6 It has been estimated that approximately 40% of all trial convictions in Louisiana are rendered by a non-unanimous jury.8 All 134 delegates in attendance at the Louisiana Constitutional Convention of 1898 (“the Convention”) were white, and none remained “secretive about their purposes.”9 In his closing address at the Convention, Judge Thomas Semmes stated: “We met here to establish the supremacy of the white race.”11

[w]

- La. Sec’y of State, Statement of Proposed Constitutional Amendments: November 6, 2018, https://www.sos.la.gov/ElectionsAndVoting/PublishedDocuments/ProposedConstitutionalAmendments2018Summaries.pdf (last accessed Oct. 23, 2018).

- [La. Const. Ann. art. I, § 17; La. Code Crim. P. art. 782(A).

- Id.

- Fed. R. Crim. P. 31(a).

- Or. Const. art. I, § 11; Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 136.450; see also State v. Lomax, 406 P.3d 94, 99 (Or. Ct. App. 2017).

- See, e.g., State v. Mack, 12-0625 (La. App. 4 Cir. 5/6/15); 162 So.3d 1284, 1288, writ denied, 15-1119 (La. 5/13/16); 191 So.3d 1054.

- Jeff Adelson, Gordon Russell, and John Simerman,

The split-jury rule was introduced in the Louisiana Constitution of 1898 as “part of a raft of deliberately discriminatory measures” fueled by the racial animosity of the Reconstruction era.7State v. Hankton, 12-0375 (La. App. 4 Cir. 8/2/13); 122 So.3d 1028, 1033, writ denied, 13-2109 (La. 3/14/14), 134 So.3d 1193.

- Id. at 1034.

- Official Journal of the Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of La. (“Official Journal”) at 374-75 (Feb. 8, 1898), Judge Semmes was followed by Judge Ernest Kruttschnitt, President of the Convention, who openly scorned the equality demanded by the Reconstruction Amendments:

We have not drafted the exact Constitution that we should like to have drafted; otherwise we should have inscribed in it, if I know the popular sentiment of this State, universal white manhood suffrage, and the exclusion from the suffrage of every man with a trace of African blood in his veins. We could not do that on account of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and, therefore, we did … what has been referred to approvingly by the Supreme Court of the United States, in the late case of [Williams v. State of Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213, 222 (1898)] as … “swee[ping] the field of expedients,” but they were permissible expedients, and that is what we have done in order to keep the negro from exercising the suffrage. What care I whether the test we have put be a new one or old one? What care I whether it be more or less ridiculous or not? Doesn’t it meet the case? Doesn’t it let the white man, and doesn’t it stop the negro from voting, and isn’t that what we came here for?10Id. at 380.